gary panter

gary panter gary panter

gary panter

Taken from "jimbo - adventures in paradise" (1988):

Gary Panter was born in Durant, Oklahoma, and grew up

in Brownsville and Sulphur Springs, Texas.

a painter, commercial artist, and designer as well as

cartoonist, he is the recipient of two Emmy Awards for his setdesigns for

"Pee-Wee's Playhouse". His work has been exhibited in Japan, Sweden,

Spain and France and in galleries across America. He was one of

the earliest contributors to "Slash", and his work has appeared in

"Time", "New York", "Rolling Stone",

"Raw", "Spin", and many other newspapers and magazines."

Around 1979 Warner Brothers asked him to do a couple of covers

for Frank Zappa albums.

Gary Panter also recorded with the Residents.

Frank Zappa appears in Gary Panter's graphic novel "Jimbo in Purgatory". The book also includes a (one-page) list and drawings of Gary Panter's favourite vinyl recordings. It includes The Mothers Of Invention with "Uncle Meat", Captain Beefheart's "Clear Spot", an Edgar Varèse album, The Fugs, Pink Floyd, and more gems.

"Jimbo's Inferno", another graphic novel, and part two of Jimbo's adventures, also includes another (one-page) list & drawings of Gary Panter's thirty-three 'best loved vinyl recordings'. The list includes Zappa's "Lumpy Gravy", Captain Beefheart's "The Spotlight Kid" and The Residents' "Duck Stab", just to name a few.

publications / comics

|

|

|

Frank Zappa appears in "Jimbo in Purgatory" |

|

|

|

|

| the cover of "Jimbo in Purgatory" | the cover of "Jimbo's Inferno" |

|

|

| Ralph Records Catalogue no.6 - 1980 | Ralph Records Catalogue no.7 - 1981 |

discography

| gary panter: pray for smurf (1979, 7", usa, ??) |

||

| Jay Condom / Gary Panter- Durchfall frum der

Colahaus (1980, 7" EP: Pandomoniax/Protoceratops//Old East Texas Plankton/Pandomoniax) |

||

|

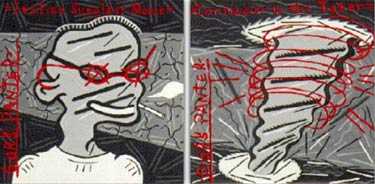

Gary Panter- Tornader to the Tater / Italian

Sunglass Movie |

||

| Gary Panter / Jay Cotton- One Hell Soundwich (1989) |

||

|

devin flynn

and gary panter: devin and gary go outside |

||

| gary panter, ross goldstein & devin flynn:

four corners (2011, lp, usa, artibtary signs) |

||

| devin, gary & ross: honeycomb of chakras (2013, 2lp, usa, feeding tube records) = devin flynn, gary panter and ross goldstein |

album cover art

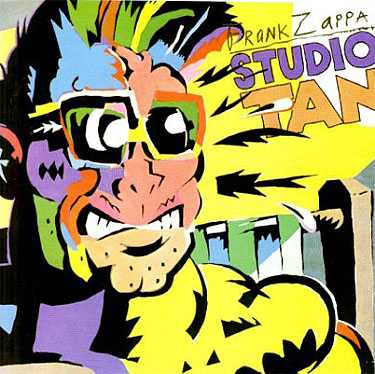

| 1978 |

Frank Zappa- Studio Tan |

|

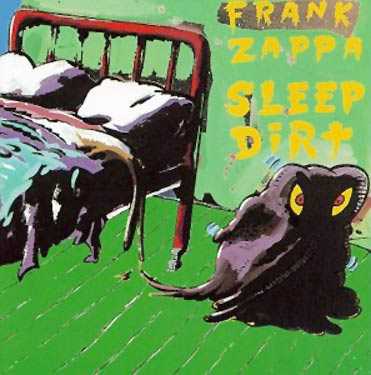

| 1979 |

Frank Zappa- Sleep Dirt |

|

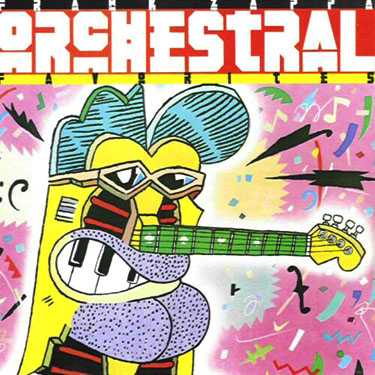

| 1979 | Frank Zappa- Orchestral Favorites |  |

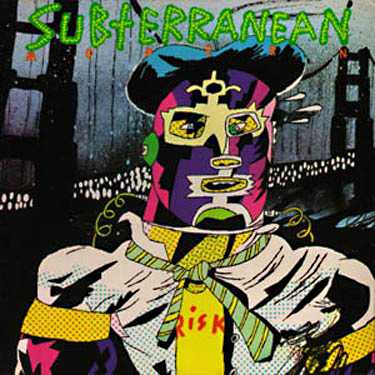

| 1979 | Various Artists- Subterranean Modern |  |

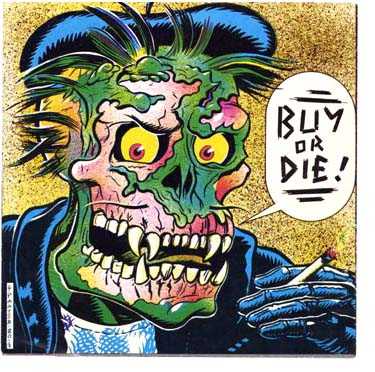

| 1980 | Various Artists- Buy Or Die |  |

| 1981 | Renaldo & the Loaf- Songs for Swinging Larvae | |

| 1981 | DB Cooper- Dangerous Curves | |

| 1981 | Ian McLagan- Bump In The Night | |

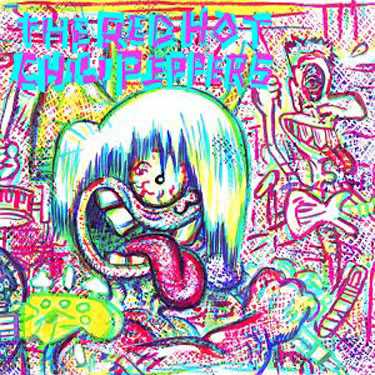

| 1984 | Red Hot Chili Peppers: s/t |  |

| 1988 | Half a Chicken- Food for Thought | |

| 1989 | Duke Elington- The immortal 1938 year | |

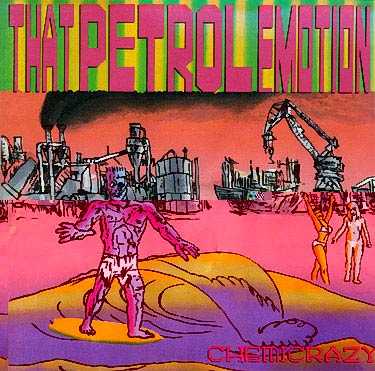

| 1990 | That Petrol Emotion- Chemicrazy |  |

| 1993 | Soluble Fish- Chem Imbalance Lo-Fi Comp | |

| 1993 | Various Artists- DIY - We're Desperate - The L.A. Scene | |

| 1993 | Various Artists- Punk II: Faster and Louder | |

| 1995 | Various Artists- Saturday Morning Cartoon's Greatest Hits | |

| 1995 | Steel Pole Bath Tub- Scars from falling down | |

| 1998 | Bongwater- Box Of Bongwater | |

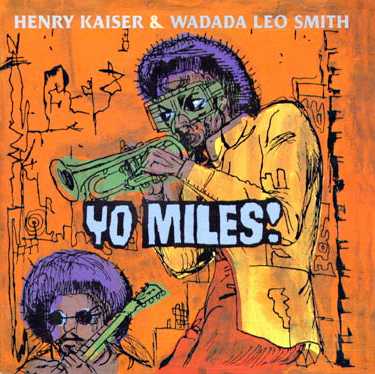

| 1998 | Henry Kaiser & Wadada Leo Smith- Yo Miles! |  |

| 1998 | Doc Watson & Merle- Lonsome Road | |

| 1999 | Tito & Tarantula- Hungry Sally & Other Killer Lu | |

| ???? | Various Artists- Spooky Tales of Now (cd with comicbook) | |

| ???? | Bongwater - Too Much Sleep |  |

| ???? | Various Artists: A Tribute To Godzilla |  |

| ???? | Paul Flaherty & Chris Corsano: The Hated Music |  |

| ???? | Various Artists: Help Us Get High |  |

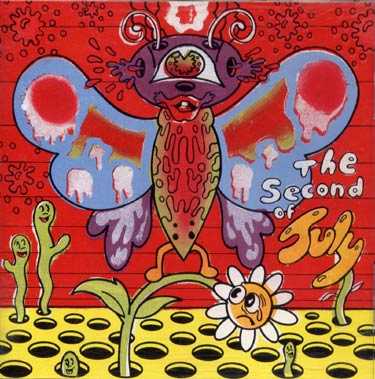

| 1995 | July: The Second Of July |  |

| ???? | Pee-Wee Herman: The Pee-Wee Herman Show |  |

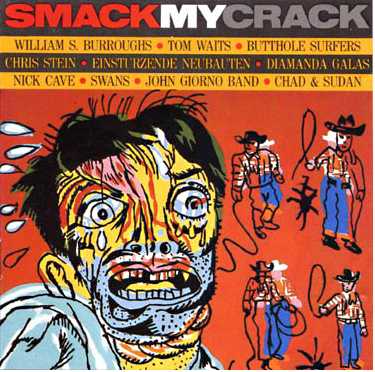

| ???? | Various Artists: Smack My Crack |  |

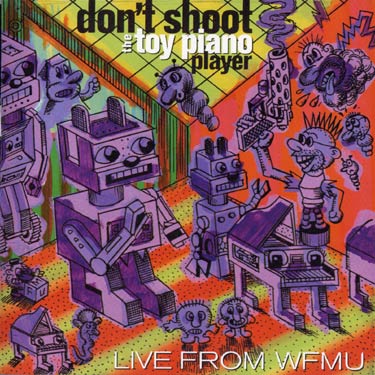

| ???? | Various Artists: Don't Shoot The Toy Piano Player - Live From WMFU |  |

PANTER'S PLAYHOUSE

Punk artisan GARY PANTER paints himself into a

corner.

by Steven Cerio

If GARY PANTER

knows anything he knows art is for kids, art is recreation, art is candy. As a

child he found his salvation in the monster matinees as Bazooka Joe read the

scriptures. With his left hand clutching a brush, his right has been loosening

the stiffened rigor mortis joints of the festering art world and slapping the

anal retentive cartoon establishment silly.

Though probably best known for his work on Pee-Wee's

Playhouse in the late 80s, Gary was humbly spawned by the ruckus of the long

expired LA Punk scene where he graced the pages of Slash and polluted the

streets with his Punk show flyers and now- classic self-published comics like

The Asshole. These years earned him the modest of title of "King of Punk

Art" and christened by Robert Williams as "King Of The

Preposterous."

Spurred on by design great Cal Schenkel, he moved up

from his covert works and into the dazzling arena of commercial art, creating

covers for the heavenly super-human Frank Zappa, Red Hot Chili Peppers and the

much undercredited Snakefinger. He endlessly

creates those album covers which demand to be fondled and obsessed over in

harmony with the music. Cartooning all the while, Gary created

"Jimbo," everyone's favorite post-nuclear boy. He also coughed up

Daltokyo, an urban deathscape haunted by the last Ford Mustang along with the

ever- resourceful Okupant X. The comics generated both love and misunderstanding

from the comics world with their disjointed narrative and seemingly haphazard

execution, something the butt-clenched conservatives feared and will to continue

to fear for centuries to come. Panter made his way to Mr. Reubens and designed

the set for Pee-Wee's Playhouse, a sometimes frightening world of grinning

pterodactyls, chattering robots, and an adoring chair, Chairry, that now adorns

Gary's daughter Olive's room. It also birthed a regiment of toys the likes of

which the world had never seen  before.

Three Emmys later Gary skipped town and left the show's host with penis in hand.

before.

Three Emmys later Gary skipped town and left the show's host with penis in hand.

Gary was allowed to return full time to painting, his

first love. Churning out canvases with the fervor of a child blessed with a

sugar high, he introduces a new breed, a strain of reckless psychedelic

retardation dripping with childhood delusion and toy greed. This is the new

Psychedelia, unwieldy, unembarrassed and difficult. Logos from cereal boxes and

candy wrappers surface like jewels. Each piece hops and bubbles with unspoken

logic, giggling with an inarguable wise ass tone.

Gary works and lives in Brooklyn where he is currently producing a series of Jimbo comics (three already complete) for Matt "The Simpsons" Groening's Bongo Comics. He is also working on a proposal for an animated show developed from characters he and Ric Heitzman developed for their children's comic, Kaktus Valley.

SECONDS:You took off during the LA Punk scene, right?

PANTER: I got to LA at the end of '76 and started seeing flyers around, and saw Slash Magazine. It fit in with what I was doing, jaggedy-line stuff. I had sketchbooks full of that stuff that I'd been trying to sell back in Dallas. Then Punk happened. First I thought it was a bunch of creepy kids. English Punk really grossed me out. It had the effect that they expected to have. I realized afterwards that it wasn't just a bunch of Nazi retards.

SECONDS: Was The Asshole the first thing that you got attention for?

PANTER: I published a thing called Hup when I first got to LA, a self-published quick print comic about a Godzilla samurai guy on this big three-horn triceratops tractor. Then I did book called Alamo Courts. It was mostly written work and it was a love story between two rednecks in the future. Maybe The Asshole might have come after that and 101 Views Of The Asshole. It seems like there was more stuff. I guess I started drawing Jimbo for Slash after the first comic.

SECONDS: Robert Williams points that out as being the first time he saw your work.

PANTER: That was a few years after I'd been in LA. When I found out what was happening and found bands to like, I tried to do flyers and draw in Slash.

SECONDS: Robert Williams calls you the father of Punk Art.

PANTER: I don't know what to say about what Punk Art is. My work has a lot of obvious influences from Aborigine Art on up through the stuff that looks similar to - but I don't feel is influenced by -Êlike Ben Shahn. My influences were more Dubuffett and Cal Schenkel, who did the Zappa covers, and David Hockney. I just ended up liking the shaky weird stuff because I was uncoordinated and not slick. I didn't have the muscle control to do real slick work.

SECONDS: So you have a new comic coming out?

PANTER:

I think at the end of the year I'll start a Jimbo quarterly comic that will

feature many of my characters under the banner of Jimbo. Jimbo will be on the

cover and then Henry Webb and all these other characters will be in there, too.

They're familiar to me, but they're still unpublished so they're unfamiliar to

everyone else. There's these hillbilly brothers that are cousins of Henry, an

angry chicken, and this gang called the Soul Pinx that wear these little

dogheads. I guess it's like a soap opera in a way. I skip around between

different characters but I don't forget about them. I come back and advance and

interweave their stories. It seems to have enough closure from issue to issue to

not feel too unstructured. Right now I've finished three thirty-two page comics.

It's real fun.

PANTER:

I think at the end of the year I'll start a Jimbo quarterly comic that will

feature many of my characters under the banner of Jimbo. Jimbo will be on the

cover and then Henry Webb and all these other characters will be in there, too.

They're familiar to me, but they're still unpublished so they're unfamiliar to

everyone else. There's these hillbilly brothers that are cousins of Henry, an

angry chicken, and this gang called the Soul Pinx that wear these little

dogheads. I guess it's like a soap opera in a way. I skip around between

different characters but I don't forget about them. I come back and advance and

interweave their stories. It seems to have enough closure from issue to issue to

not feel too unstructured. Right now I've finished three thirty-two page comics.

It's real fun.

SECONDS: Who's going to be putting that out?

PANTER: Bongo Comics in association with Matt Groening. They put out The Simpsons comics. Jimbo #1 should be out at the end of the year.

SECONDS: How long were you out in LA?

PANTER: For about nine years. From '76 to '85.

SECONDS: How do you think the LA art scene is different from New York?

PANTER: I think about artists all over the world - LA has a bunch of them and there's a bunch out in the country; they're all scattered out. Where New York has impact in just having all these galleries and publications that this work might flow through. All that stuff's fallen apart to a great extent. There's no art being run through the art system. The channels right now are advertising and underground comics, where you can get information out and show experimentation and change.

SECONDS: Did they name a park after you in Japan?

PANTER: It's called Gary Panter Square. I never saw it. It's in Nagoya. I saw a picture of it. It was like a little snack bar surrounded by video monitors with a DJ booth. I guess it must be like a cafe. You go there and have a drink and they show videos. They had videos made of comics with the colors all changed and music behind it. I guess they show rock videos and maybe someone was doing experimental films or something.

"I was the go-between for Pee-Wee and forty companies at one point."

SECONDS: Did you have any sculptures there?

PANTER: No, I had nothing to do with it at all. I had an agent, Mr. Ishii, who brought me to Japan and promoted me in Japan. Evidently I had fans in Nagoya.

SECONDS: Is that exciting?

PANTER: It's neat. I wish I could have gone there and looked at it. I never really felt welcome to go there. No one ever asked me. If I went there it would wreck it somehow. Every once in a while I run into someone who's seen it and they say it's a little cafe. It's like a big "X". There's a big X wall and there's tables around the X and then there's video monitors and a DJ booth behind the glass.

SECONDS: How did you happen upon the Pee-Wee Herman gig?

PANTER: I was approached by someone from Pee-Wee to do a poster for a stage show he wanted to do. It would be for free - I don't remember, maybe I got paid for it. I didn't know who he was and I went and saw him at the Groundling Theater and thought he was really funny. I met him and told him I wanted to do the design for his stage show. So I designed the stage show. It was an HBO special, it was on stage at the Roxy Theater and the Groundling Theater for about a year in LA. A lot of people worked on it. Jay Cotton did the music for the first Pee Wee shows in LA. Then he and I got a development deal at Paramount and we had an office for eight months and we wrote a script called Pee-Wee's Big Adventure, but they turned it down. Jay got another development deal and he wrote it with Phil Hartman. That's the one that became the movie. I was approached later to do the TV show. He sold the show and asked them to call me and finally they did.

SECONDS: You designed the furniture on the set, right?

PANTER: There were other designers on the show, Wayne White, Ric Heitzman, Phil Trumbo, Greg Harrison - there were a lot of people designing the show but I was the head designer.

SECONDS:You did a lot of toys and trading cards too.

PANTER: I was the go-between for Pee-Wee and forty companies at one point. We did this promotion for Penny's where we designed 200 garments and belts and sneakers and bags and jeans and jackets - every kind of stupid thing you could imagine.

SECONDS: You've done quite a few record covers. Is the commercial work satisfying for you?

PANTER: It's not the same as the paintings or comics I draw for myself. It's just more fun to do something that I want to do. If I'm doing something for a band I really like, it's exciting. Professionally, I always try to do something good. With the Chili Peppers, I liked them and knew them a little bit and I got to do two covers for them. You get to know bands if you do album covers. But Eugene Chadbourne, I just called him and volunteered to do a cover because I was a fan of his work and the same with Bongwater. I liked a lot of the stuff that Kramer was putting out, so I just asked if I could do a cover and I did one for The Walking Seeds and some type on Too Much Sleep.

SECONDS: How did the Zappa covers happen?

PANTER: Those were unauthorized and it was really a strange moral dilemma with some guilt attached. Maybe I'm dramatizing the thing but Zappa wanted to put out a three-record set called Lather and Warner Bros. wanted to dump these records on the market, and I didn't know that. They hired me to do covers and I was wondering why I wasn't meeting Zappa because I know he's a total control freak. Then I found out while I was doing the third one that they were unauthorized, and that's why I wasn't meeting him. He was going to sue Warners. I'd written him fan letters and I'd met Cal Schenkel when I first went to California. I wrote him after I did those covers but I never heard from him. Matt said he liked the images okay and Gail used them again in reissuing the records so I guess it's okay. I liked the music a lot and I'm a total Zappa fan since high school.

SECONDS: What else do you listen to?

PANTER: I like Beefheart. Right now, I'm listening to Nurse With Wound, 60s stuff, and 80s Virgin Prunes stuff. I get a lot of the records I never had before in garage sales. I just got a Jethro Tull record.

SECONDS: For a dollar, right?

PANTER: Yeah. In perfect shape. And I just got the soundtrack to The Bible by some Japanese composer. It's little bit like a Godzilla soundtrack. And I make radio tapes where I just take little bits off the radio - listen to clips of ten seconds of a song and a commercial and listen to it a thousand times, and get rid of things and add things in. I like Negativland and Eugene Chadbourne. Psychedelic and neo-Psychedelic and Concrete music, Electronic music.

SECONDS: You play music yourself?

PANTER: Yeah, I play in a retarded kind of way.

SECONDS: You've done a couple of records.

PANTER: I had the opportunity to put out some records. The music I have out isn't schooled or anything. I would make up these songs in my room and then I'd get a chance to go into a studio and record them. The first time I would ever hear them would be when it was going on tape. It was very amateurish and weird. It goes along with the roughness of my other work. I shouldn't really be putting out records anyway.

SECONDS: Why's that?

PANTER: I just think it's embarrassing to put out half-assed dopey records. Anyway, I enjoy doing it. I love doing the package stuff. Some people even like them occasionally.

SECONDS: You were hooked up with The Residents for a while. The Ralph Records ads used to scare the pants off me. It was as if there was some retarded guy they kept in the basement.

PANTER: They did have a retarded friend who's left-handed, can't quite put things together in the right way, and not really trying that hard to make it. I've always been interested in creepy stuff since Famous Monsters Of Filmland and monster movies. I remember seeing an ad in the paper for The Land Unknown and making my parents let me go see it when I was six. It was a double feature with The Curse of Frankenstein and I just remember having the shit scared out of me.

SECONDS: Are you putting a lot of your energy into painting now?

PANTER: I've always been painting. I always drew and my father painted when I was a baby, so it put in my mind when I was real young that I wanted to be a painter. When I was in high school I was painting big paintings out in the garage and trying to leave home so I could become a Hippie.

SECONDS: You keep saying "left-handed." What do you mean by that?

PANTER: Well, I think that right-handed people probably have a different kind of control or often have a more organized mind - or a mind that's organized in a different way - from a left-handed person. The left-handed person really does have difficulty interfacing with the spin of the world. I draw with fountain pens but they're just so obviously not made for me and I don't really have any left-handed fountain pens. I probably wouldn't know what to do with one if I had one.

SECONDS: But you have a right-handed guitar.

PANTER: When I first started out, I had to choose. I decided to just do it regular and play it normal. I've haven't often played with people, so I'm not playing things to the beat a lot. I'm playing what I remember, spilling it out over and over. When I do play with people, I have to work hard to stay on the beat, and I don't tend to rehearse my stuff through. I'm grown-up, I should have mastered these real simple things but they're still eluding me. I've mastered a lot of other things. It's like a person that can play the drums. It's very natural for them to establish a meter and get in a groove. I have a real hard time doing that.

SECONDS: What artists did you enjoy as a kid?

PANTER: Walt Disney and Picasso and Dali were probably the first guys I became aware of. Well, I was aware of cartoonists like Al Capp and people that were mysteriously slick and stylized. It was like, how do they draw like that over and over? My father could kind of do that. He never did cartoons but he had a more controlled drawing. Then, I didn't want to go out for recess so I looked at every book in our local library about Art and then I went to college and did the same thing. There was a really big library at this little Texas college - I just looked through all the Art books and it really helped. Finally, big fat books on Prehistoric Art and big fat books on Polish circus posters - everything.

SECONDS: To you, what makes a good painting?

PANTER: Whether you keep wanting to be around it and it doesn't nag at you. I want to make paintings that I want to be around. I would like to wake up every day and when I looked at them there would be something else to see in it. There's a lot of horrible art and luckily there's a lot of good art too. People hate art because they haven't been able to pick the good stuff out from the hokey horrible shit.

SECONDS: Do you consider yourself part of any movement?

PANTER: I'm merely into the future. I've always been interested in those things and interested in the sequence that they happened - trying to look outside at what's recorded into vernacular art and Folk Art and have a broader look at things; to just look at stuff like a Martian and try to imagine new combinations. It doesn't really have to be a GE idea of progress, just invention for the fun of it. The way you'd apply the stuff would help you change the way you could live. You have to imagine all of this in order to pick out what can actually transform the living. I'm waiting for the living to be transformed. I think it's going to get real transformed.

SECONDS: What are the bare necessities for you to be able to work?

PANTER: Just a pencil and paper. I do a lot of what a prisoner would do. I make all these gigantic plans in sketchbooks; immense monstrous Jack Kirby scale plans. It would really be nice to do some of them. You just get a different feeling from doing something like that and you can actually find out how successful or unsuccessful it is by full-scale mockups. It'd be fun to have some money or patronage and make some of these things.

SECONDS: When did you start leaning towards childish images?

PANTER: In 1972, I had my little epiphany of having moved away to college, manufactured my own situation and then realizing I had constructed an advance nursery for myself with ducky hankies and tin pails and Buddhist block printing and all this crazy shit. I just started looking at myself as a prototype of myself. There was a lot of Art being done that referred to the childish. There was a lot of infantilism in Dubuffet and Hogarth.

SECONDS: It seems you have the influence of Art Brut.

PANTER: Growing up near Mexico and then in this Fundamentalist religion had a lot to do with early input and how I could process information. I saw some things in Brownsville, Texas like a lot of Mexican Folk Art and Mexican puppets and pottery; nursery school stuff. You'd be driving through this giant orange grove and suddenly they'd be a fifteen-foot-tall plywood cut-out of Porky Pig. To me that had the strength I could get later from a Motherwell. That's one of my inspirations and I started making things like that. I have plywood cut-out paintings of other images. Someone could say I was trying to recreate my childhood or something. I don't really think I am, I think I'm just trying to make a list of the things I've come across that are pleasant, and accumulate them together to make something more pleasant.

SECONDS: Did you analyze your images?

PANTER: I look at it more like it's dream time or how you would interpret a dream. I could be analytical about it but I generally don't choose to be. I just like to find things that are evocative to me and then match them together. Like making a perfume or something. You get all these different smells or color sensations and you array them and try to make something that will make people standing next to it feel funny, or just nice and cool. That's what I like about big paintings. People are critical of careerist painting but I always liked standing next to some of those big Mexican paintings.

SECONDS: It's the size that does it for you?

PANTER: It does, yeah. It's a room-sized thing and not like a book experience.

SECONDS: How do you feel about the use of drugs in art?

PANTER: Well, I would just encourage people to watch someone else take it first. Try to figure out what you got your hands on. It could be extremely dangerous and fuck your head up forever. On the other hand, it's part of a spiritual quest like it always has been. The idea of the Indians going out and having visions, how do you think they were having the visions? I'm sure they were starving themselves but they must have been eating a lot of mushrooms and smoking pot. That's what artists are supposed to do. I think it's good to have a healthy fear of certain drugs. But there's certain other drugs that are useful, friendly, helpful"

SECONDS: I often describe your work as being "retarded" to people and they don't understand that as a compliment. How do you feel about that adjective being used?

PANTER: My work is definitely out-of-control so it would apply to it in the pejorative sense. I think it's just after something else besides slickness and technologically-perfect vision. It's after what I can get going in different directions. Terry Mann is this guy whose idea is good/bad. There's this beautiful kind of badness, so you can get worse and worse and stupider and stupider and uglier and uglier, and if it's presented in the right way with the right content it could have this transcendent aspect to it - that's what I would be after, something that's wrong just right. Not even controlled. Just try to be at one with nature, see what's in your head and see if you can get it out, and then analyze it. When I was really young I would sit around with some ideas or ideas I didn't know I had, and I spent a lot of my time going, "I don't know what to do, I don't have any ideas!" I had to go out and try really hard to get something going. I'd go out and draw every line of every leaf in the backyard and do it and do it and strive to have some vision - whether you do drugs or not, and intensify your experience. Over a period of years your vision does change, and all of these simple premises you were able to observe for having done them long enough get incredibly complicated and rich. You wish you could live a thousand years just to see what would happen to it.

SECONDS: People in the art world like you to think they've always had visions and ideas.

PANTER: People do decide on a signature style rationally. I think that people do have these incredible rich, ideal lives that they don't know about. I think your average dork has this incredible movie going on that he watches a few minutes every day and forgets about as soon as the daydream is over. The dorkiest guy is sitting there watching TV and he spaces out and suddenly he sees a one-wheeled fire truck filled with feather dusters headed to the sun for one second. Then he forgets about it and it's of no consequence. As an artist, you're just trying to open those doors more of the time and control it a little bit.

SECONDS: It's said that artists are people with a vision.

PANTER: I think an artist is someone who's interested in making art. That's all it takes to be an artist. Everyone is variously equipped to do it. I think everyone is well-equipped to have visions. It's a link to this part of your brain you would go to on LSD. The shutter opens for one second, this little pun comes out and the shutter goes back down. That's what's great or dangerous about doing something like LSD - can you really take the shutter being open for twelve hours? Is it really going to be a constructive thing to do? Maybe you could not take any drugs and just work up to it with these visual explorations.

SECONDS: Some people treat drugs like a learning experience, try to take what they can from it, and learn how to look at things differently. Do you think that can be done?

PANTER: Oh yeah, absolutely. That's what people commonly use drugs for and what they're good for. I have known a few instances where some uptight straight kid in small town took LSD and blew his brains out six months later. I've known a much more amazing amount of people where nothing ever bad happened to them aside from a few bummer trips that made them think twice. I don't have to go into it in print because I've raved about it too much. But I had this incredibly strong bad acid trip in '73 that has preoccupied a great deal of my life just because of the strength of the memories. A certain amount of what's on my daydream screen is that acid trip. For a year or so something was saying "boo" to me all the time. I could hear a cat breathing by my face for a year. I couldn't stand to hear gas jets on a stove. I've always had a lot of auditory hallucinations. I'm going to sleep and hearing jets and doors slamming.

SECONDS: Do you always have music on?

PANTER: Matt Groening's commented that I don't listen to music to soothe me but I think I do. I listen to a lot of aggressive music and weird music.

SECONDS: A lot of people wouldn't think of Zappa and Beefheart as relaxing.

PANTER: Too many notes.

random notes

(b. 1950)

Texas-born, New York-based artist whose career took off alongside the

do-it-yourself amphetamine burst of the late-'70s Los Angeles punk scene. A

virtuoso of scratchy drawing and painting, Panter works a fine line between

"high" art and the commercial spontaneity of countless illustrations

and album covers.

Beginning in the pages of the L.A. proto-zine Slash, his Jimbo is published by

Simpsons creator Matt Groening's Bongo Comics Group. Responsible in great part

for the surreal visual impact of Pee-Wee's Playhouse (1986-1991), Panter has

described his work as a conjunction of Mexican mural art and Jack Kirby's

Fantastic Four. In addition to his many side projects, Panter edits the comic Go

Naked and has recorded a pair of albums, Savage Pencil Presents "One Hell

Soundwich" (1990), with longtime accomplice Jay Condom, and Pray for Smurf

(1993).

1981 Gary Panter- Tornader to the Tater b/w

Italian Sunglass Movie

The Residents play backing instrumentation on this single and helped with the

arrangement and mixing. Panter, who had created the cover for Ralph Records'

Subterranean Modern, did this single's cover as well. The cover folds out into a

full color 20" by 28" poster. Both songs were included on Gary

Panter's "Pray For Smurf" LP on the Overheat label in Japan, and

"Tornader to the Tater" only was included on his "One Hell

Sandwich" LP on the Blast First label in the UK.

From:

Franz Fuchs

Gary Panter

interview

"TCS: How did you get involved with album cover design?

GP: When I moved to LA in ‘76, I was desperate to get

work, and I started to do little spot illustrations for some record companies

and magazines, or just showing my weird paintings. I didn't know it, but Frank

Zappa was on tour, and Warner Brothers decided to get him off the label. The way

they were doing it was issuing a breaking-up four- album set called

"Ladder." So they issued (while he was on tour) albums in very rapid

succession. I just got a call from an art director that I knew, asking me if I

wanted to do a Zappa cover, and I said, "YES!" But I didn't hear

anything from Frank Zappa; I never met him.

Then the art director called me a month later, and asked if I wanted to do

another Zappa cover, and I did it, and I still didn't meet Zappa. I was

thinking, "What is going on? Is he control freak, where is he?" And

when they called me for a third one, I said that I don't know what the deal was,

and they explained. So I did the cover, and I think that he ended up liking

them.

OK, years later. Matt Groening became friends with Zappa, and Zappa told him he

liked the covers. I never met Zappa, which was too bad."

Note

Gary's "Ladder" faux-pas :-)

The whole interview can be found at:

http://www.thecomicstore.com/merchant/garypanter.htm

From:

Kristian Kier (KrKier@rocco.wupper.de)

I searched info about a book about the Residents, mainly was interested how many

books were printed. No, haven´t found the specific information, but on the

(unofficial) Residents pages at http://www.residents.com/ I found the

information about a collaboration/info about a single release by Gary Panter,

the painter who made the cover art of Frank´s OF/SD/ST for Warner Brothers. If

I understand correctly he´s also a musician?

Look here: http://www.residents.com/collab/panter.html

Regards

Franz Fuchs

From:

Patrick Neve

Gary Panter did the artwork for what has come to be known as the

"ugly" Zappa covers. Not

because they were unattractive, but due to the fact that they were unauthorized

decisions on the part of Warner Bros.

There used to be a nice little interview with Gary where he discussed his

thoughts about the Zappa album covers he did.

It seems to no longer be online anywhere; I beleive the IUMA was hosting

it for awhile. Dr. Istvan Fekete

(IFekete@daten-kontor.hu) forwarded the following page to me, and since it was

exactly what I was looking for, I am hereby illegally posting it.

If you are with Seconds or IUMA and have any problem with this posting, I

will comply 100%. In the meantime,

I don't believe this appears on the web anywhere, and it really oughta be. -patrick

From:

Franz Fuchs (fr_fuchs@yahoo.de)

From the Fantagraphics (http://www.fantagraphics.com/) e-Mail

Newsletter:

* COLA MADNESS By Gary Panter -- $24.95 ($37.45 in Canada) -- Funny Garbage

Press has unearthed one of the great comics finds of the last 20 years: an

original, never before published 200 page "Jimbo" graphic novel drawn

by Gary Panter in 1983. COLA MADNESS is the most ambitious and sustained comics

narrative of Panter's career, and it's remarkable that it has remained hidden

for so long. The acknowledged "Father of Punk Art," contributor to

RAW, and co-creator of PEE WEE's PLAYHOUSE,

Panter originally conceived and drew COLA MADNESS for a Japanese audience, and

as such utilizes a simple two-panel per page layout and employs an

unusually-accessible narrative style to tell the story of a mysterious tribal

figure named Kokomo, who eventually falls asleep to dream a wild, 150-page

picaresque 'interlude' starring Jimbo and Bob War. In this allegory of man

against nature, the two careen through a synthetic fantasy world where

Jack-in-the-Bell-Mc-Taco restaurants mask sewage treatme! plants, while a nature

symbol gone berserk unravels everything. The book comes full-circle upon

Kokomo's awakening, as Panter infuses equal parts Jack Kirby, Phillip K. Dick,

and punk rock to create one of the best graphic novels to come out in any year.

Informants:

Honeymoon Jam (yourface@myass.com

| Juxtapoz issue #48, jan/feb 2004,

includes a 7-page interview with Gary Panter |

|