harry andronis

harry andronis harry andronis

harry andronis

Reprinted from "Zappa!", published in '92 by Keyboard and Guitar Player magazines:

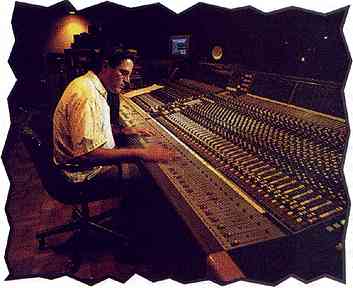

Harry Andronis: Mixmaster Outside The Kitchen

"He says, 'anyone who has a coat like that must know

something,' and he hired me," laughs Harry Andronis, house mixer for Frank

Zappa since the 1988 Broadway the Hard Way tour. Was that coat of many colors?

Lined with French postcards? Why special enough to warrant on-the-spot hiring?

"Who knows?" Andronis muses. "It's really nothing. Just one of

those heavy, East Coast overcoats."

As

with many Zappa hirings, that glib comment was in fact the end, not the flip

beginning, of a screening process that had already been completed after a strong

recommendation to Frank by one of his most trusted workers, Marque Coy, then in

charge of monitor mixes and now manager of Joe's Garage.

Coy

and Andronis had worked together in the '70s for Chris De Burgh, a superstar in

Europe (if barely an opening act in the U.S.). In 1987, while Andronis was

working on a Shadowfax LP down the street from where Zappa was rehearsing, he

convinced his old road buddy to sneak him in to watch. Emboldened on discovering

that no house mixer had yet been hired, Harry told Coy to throw his name into

the hat.

A

longtime Zappa fan, Harry was first introduced to his music at age 13 by a

cousin who sat him down with Hot Rats. "I thought it was brilliant,"

he recalls. "I was always moved by what was happening in the tracks

sonically and musicallyjust the sound of different instruments, and he used

weird ones-bass clarinets and xylophones. It was almost like Spike Jones, only

it wasn't hysterical."

A

10-week course offered by the RIAA taught Andronis the rudiments of recording.

An apprenticeship during college at the Paragon Recording Studio filled in gaps

of his audio education. Besides learning to clean out garbage cans, he learned

how to copy tapes, set up sessions, and second in the control booth. Finally, he

was doing jingles for Schlitz, McDonald's, and United Airlines, as well as

night-time stints with rhythm and blues groups and local celebrities such as

Stix.

"Eventually,"

he states, "I got too big for my britches and too burned out, and I split

for Los Angeles." A fluke led to a position with Supertramp just as their

Breakfast In America soared up the charts, dragging the support staff up and

away on tour, and leaving Andronis to hold down the board in their demo studio,

where he worked with such luminaries as Jean-Luc Ponty and Earl Slick. In 1982

he moved on to Shadowfax, with whom he still works occasionally. "I learned

a lot with Shadowfax that applies now to Zappa," he says, "especially

early on, because they used a lot of exotic percussion. We also played a lot of

places that didn't have adequate P.A.s, and I had to learn to use the room. If

you don't have the right reverb, you listen to the room and I say, 'Okay, well,

it's got a bit of ring to it, so there it is."'

This

minimalist/improvisational approach is the I key to his work now with Zappa,

though initially, because of it, he feared his first gig would be his last.

"I think I worried Frank at the rehearsals," he explains. "The

first day, he came up and was talking to me, and I could see him looking at the

back of the console. Finally, he said,'Is everything plugged in?' I walked

around the back and looked and said, 'Yeah, looks like it. Why?' 'There's a lot

of holes here.' I looked at the stage and told Frank, 'It's a 10-piece band, and

it's pretty busy anyway. Everybody's got a lot of processing on their stuff now,

don't they?' And he went, 'Yep.' And I said, 'Most of the halls we're playing

are going to have at least 1.5 seconds of reverb time, aren't they?' And he

said, 'Yeah.' 'Most of the places are going to have 200 300 milliseconds

slapping off a wall somewhere, aren't they?' He said, 'Yeah.' And I said, 'Well,

I don't think I need anything, do I?' And he said, 'Well, maybe not.'

"You

see; I had decided I wasn't going to use a lot of effects. Since 1973 I'd seen

at least one show from every one of Frank's tours. I was never terribly

impressed by the sound. I felt it was almost insulting, even painful at times.

They used to tear apart the house studio and bring it on the road. So in the

front, they'd have chambers, delays, compressors, auto pans, gates, Aphexes, and

all that sort of stuff-and it sounded that way. Plus, there seemed to have been

high-end deprivation, because they used to bring these extra piezo packs and

throw them on top of the stacks for extra high end So the first thing I did was

get rid of all those effects.'

Andronis

actually had brought an old Scamp effects rack, an FPX and an AMS delay for

Zappa's comfort, but he ended up using only a little reverb for a couple of

outdoor shows. "Otherwise" he

recalls, "with ten guys playing these arrangements which had 128th-notes

flying and bouncing all over the place, the last thing they needed in a hall was

some added reverb and delay. I'm out there to make Frank Zappa sound good-

whatever it takes, and I think the people that went to see those '88 shows got

to see the finest performances they'll ever see.

"I'm

very happily employed. People are sometimes intimidated by Frank, because he

looks you straight in the eye, but he's amiable and fun. I've always had a good

time, if for no other reason than to be able to get my hands on this kind of

music. And the humor factor is great When [evangelist Jimmy] Swaggart got

busted, there was high morale for a couple of weeks. That's always what makes

you want to work hard, because you just know that something special might just

happen any night. Not to mention, having the acknowledgment of someone like

Frank Zappa that I know what I'm doing certainly helps my own self-esteem.

"It's

his music, he's paying you to do the gig, do it. I ran up against that real

early, because the first soundcheck that we did, Frank walked in and turned on

his guitar and it was just blazing, and I didn't even have the P.A. up, so I

immediately got on the talkback and said, 'Frank, you've got to turn it down,'

and my intercom started flashing and a couple of the guys from the crew who'd

been with him for a while were saying, 'What

did you say to Frank?' 'I

told him to turn down, it's pretty

loud, isn't it?' And they said, 'Yeah, but it's his show,' and all I could say

was, 'Look, he's paying me to make him sound good, and right now he's really

loud, and it's making it really difficult for me to make anything else happen.'

Anyway, Frank walked over, and turned down, and walked back to the mike and

said, 'Is that okay?' and from that day on, he would come in and play the guitar

and ask if it was too loud or not.

"When

it comes to the gig, if you have something to talk about he'll talk to you all

day, but if you don't, then just get on with it. The guy hires you to do the

gig, and he expects you to do it, and once he knows that you can do it, he

leaves you alone. He's absolutely wonderful. He's going for a certain thing, and

he knows how to get it, and when you're working with him, he can not only tell

you what he wants, but he can also tell you how to get it. What more do you want

than to be left to do your gig? The people that stay are consummate

professionals- they know the gig."

Since

the end of the '88 tour, Andronis has continued to help Zappa remix old material

(by the end of the tour, the set list totalled nearly 130 tunes). He also has

established himself in the world of television, doing Foley work and dialog

recording for such shows as Batman, Tiny Toons, Tasmania, L.A. Law, Doogie

Howser, and Ren and Stimpy.

Andronis

looks forward especially to the upcoming Zappa events in Germany. Advance

preparation will be handled by the Ensemble Modern, which will send him

diagrams, basic room dimensions, and probable location of PA stacks.

"Because it is six-channel surround sound" he says, "we're going

to have to put double stacks on the sides [of the auditorium] in the middle, and

the board will have to be stuck in the middle of the audience. The Ensemble's

tech has played in these halls, so I'm depending a lot on him. The surround

sound is what's going to be the trick. We may feed the sound to the truck first,

because I'm still not sure how many inputs we're going to end up with. The

biggest problem is going to be that these musicians are going to be spread

around the stage in unorthodox manners, and we're going to be mixing in

six-channel surround. We'll go over a couple of weeks early and work in a

rehearsal hall with the system, since we can't get into the actual halls until

the night of the show. They'll also need to monitor the taped Synclavier

material because they're going to be playing with it at times, with it at times,

so we can expect some monitoring problems on stage that will interfere with the

miking there's a lot of stuff we haven't worked out yet.

"I

think these shows will be of severe historical importance," he concludes.

"It's Frank Zappa. The man is one of the more unique composers around, and

is one of the few who actually has the balls to try to execute something like

this. I know he would probably kill me for saying this, but to me it's really

like going to see Stravinsky conduct his orchestra- on that level. It's Frank

Zappa doing something that no one else would do. The guy truly is the

vanguard."